Revealing the Hidden Risks of QR Codes [Guest Diary]

[This is a Guest Diary by Jeremy Wensuc, an ISC intern as part of the SANS.edu BACS program]

Introduction

QR codes, those square-shaped digital puzzles found on everything from advertisements, packaging, and even restaurant menus, have made our lives more convenient. However, this blog post aims to shed light on the often-overlooked dangers of QR codes and provide insights into how malicious actors can exploit them. Understanding these risks is essential to ensure your digital safety in an age where QR codes are omnipresent.

What Are QR Codes

QR codes, short for Quick Response codes, are two-dimensional barcodes that store information, such as website links, contact details, or app download links in a graphical black-and-white pattern. It was first created in 1994 by a Japanese company called Denso Wave for tracking automotive parts during manufacturing. When scanned, the QR code can direct the user to a website, display text, or trigger other actions such as adding contact information, connecting to a Wi-Fi network, or initiating a payment.

How do QR codes work

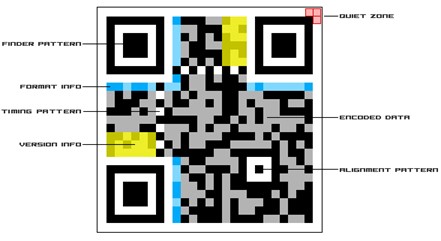

QR codes work by encoding information in a two-dimensional pattern of black squares and white spaces. The information is typically encoded as a series of binary digits (0s and 1s), and the specific arrangement of these elements within the QR code structure determines the data it represents. Here is a breakdown of a QR code:

Finder Patterns

- These are the three square patterns located at the corners of the QR code. They help the QR code reader locate and identify the code in an image.

Timing Patterns

- These are horizontal and vertical lines of alternating black and white modules that help the QR code reader determine the size and orientation of the code.

Alignment Patterns

- These are smaller square patterns strategically placed throughout the QR code. Alignment patterns assist the QR code reader in correcting distortions and tilts in the code, improving scanning accuracy.

Quiet Zone

- The quiet zone is the empty margin around the QR code. It ensures that there is enough space between the QR code and any other elements (graphics, text, borders) to prevent interference with the scanning process.

Version Information

- For QR codes of version 7 and above, a version information area is included, providing details about the QR code version, error correction level, and other parameters.

Data and Error Correction Blocks

- The central part of the QR code contains data modules, which store the encoded information (such as text, URLs, or other data). This section is divided into data blocks, each of which includes both data and error correction codewords. The error correction allows the QR code to be scanned accurately, even if part of it is damaged or obscured.

Format Information

- This section contains information about the QR code's format, including the error correction level and mask pattern used. It helps the QR code reader interpret and decode the data correctly. [1]

QR Code Attacks

The use of QR codes has surged in recent years, with applications ranging from marketing campaigns to contactless payments. However, cybercriminals have recognized the potential of exploiting QR codes to their advantage. The risks associated with QR codes include:

Quishing

- Quishing, short for QR code phishing, involves creating fake QR codes that mimic legitimate ones. Cybercriminals then place these codes on, flyers, labels, posters, or any other public or space where unsuspecting people can scan them. A good example of this happened in Texas, where cybercriminals put fake QR code stickers on pay-to-park kiosks, tricking drivers into thinking they could use them to pay for parking. Once scanned, the QR code sent the drivers to a site where they could enter their credit card information, unknowingly providing their personal info to the cybercriminals. [2]

QRLjacking

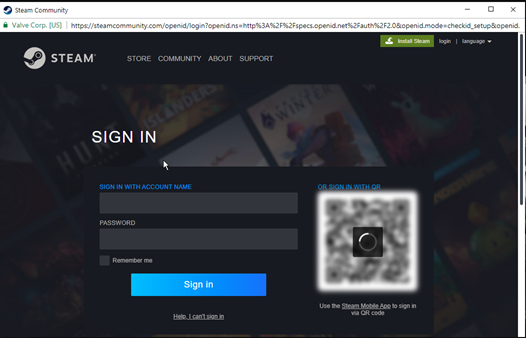

- Quick Response Login (QRL) is a user-friendly authentication method that uses QR codes for logging into websites, applications, or any other digital services. QRLJacking, or Quick Response Code Login Jacking, is a type of attack where cybercriminals create a phishing site mimicking a login page to convince the victim to scan the QR code instead of the authentic one, leading to the compromise of sensitive information or unauthorized access to an account. A good example of this happened in August of 2023 when cybercriminals targeted the Steam gaming platform and attempted to steal the user's login information so the cybercriminals could impersonate them. [3]

Malware Distribution

Cybercriminals create QR codes that point to malicious websites that distribute malware through drive-by-download attacks. Which is an attack where the website will forcefully download software on your device when you visit the website.

Scanner Apps

While most QR code scanner apps are legitimate and serve their intended purpose. There have been instances where Cybercriminals have created fake or compromised QR code scanner apps to distribute malware. A good example of this happened in December 2020 with the app Barcode Scanner. [4]

How to protect yourself

While QR codes are generally safe, there are some precautions you can take to protect yourself from potential risks associated with malicious QR codes.[5]

Use Your Smartphone's Built-in Scanner

- Consider using the built-in QR code scanning feature in your smartphone's camera app. Many modern smartphones have this functionality, reducing the need for third-party apps.

Use Reputable QR Code Scanner Apps

- Download QR code scanner apps only from official app stores, such as the Apple App Store or Google Play Store. Stick to well-known and reputable apps with positive reviews.

Update Apps Regularly

- Keep your QR code scanner app, as well as all other apps, up-to-date. Developers release updates to address security vulnerabilities and improve performance.

Verify the Source

- Be cautious when scanning QR codes from unknown or untrusted sources. Avoid codes received through posters, advertisements, unsolicited messages, emails, or from unfamiliar websites.

Check URLs

- Before scanning a QR code, manually check the destination URL or use a URL Preview Service to see the destination URL before visiting the website. If it seems suspicious or doesn't match the expected content, avoid scanning the code.

Security software

- Consider using security software on your device to provide an additional layer of protection against malware.

Conclusion

QR codes have become integral to our daily lives, but it's crucial to recognize that they come with hidden security risks. By taking the precautions outlined in this blog post, you can enjoy the convenience of QR codes while minimizing the dangers they may pose. In an era where QR codes are prevalent, staying informed and vigilant is key to protecting your digital safety.

[1] https://www.print2d.com/dt/services_consult_validation.shtml

[2] https://www.govtech.com/security/beware-of-quishing-criminals-use-qr-codes-to-steal-data

[3] https://voidzone.me/posts/a-phishing-attempt-on-steam-that-became-qrljacking/?21398

[4] https://www.malwarebytes.com/blog/news/2021/02/barcode-scanner-app-on-google-play-infects-10-million-users-with-one-update

[5] https://www.ic3.gov/Media/Y2022/PSA220118

[6] https://www.sans.edu/cyber-security-programs/bachelors-degree/

-----------

Guy Bruneau IPSS Inc.

My Handler Page

Twitter: GuyBruneau

gbruneau at isc dot sans dot edu

Whose packet is it anyway: a new RFC for attribution of internet probes

While going through newly published RFCs last week, I noticed one which may turn out to be quite useful for security practitioners, even though it is just an “informational” document. It is the RFC 9511 – Attribution of Internet Probes[1].

There are many organizations and individuals around the globe, who perform port scans of internet-connected systems belonging to third parties. Some of these are malicious actors, however, there is a significant number or well-meaning people and companies who do so as well (e.g., for the purposes of research or troubleshooting), and unsolicited packets may therefore be considered a “background noise” of the internet.

Nevertheless, there are times when one might wish to attribute a specific “scan” (i.e., unsolicited packet or set of packets) to its originator, or at least discover whether the traffic originated from a potential threat actor or a researcher/research organization - for example, if one saw that a new public IP address started to periodically scan all ports of one’s infrastructure in the last week.

So far, security analysts and administrators have had to rely mostly on WHOIS[2], RDAP[3], reverse DNS lookups and third-party data (e.g., data from ISC/DShield[4]) in order to gain some idea of who might be behind a specific scan and whether it was malicious or not. However, authors of the aforementioned RFC came up with several ideas of how originators of “internet probes” might simplify their own identification.

In the document, they define a "Probe Description File", which an originator of a scan may place in the path “/.well-known/probing.txt” on a web server, which is accessible on the same IP address, which originated the scan (and/or on a domain, to which a reverse DNS lookup of the IP address points). Format of the file is based on the security.txt file, as defined by RFC 9116[5], and should contain fields Canonical, Contact, Expires, Preferred-Languages and Description, as the following example taken from the RFC shows.

# Canonical URI (if any)

Canonical: https://example.net/measurement.txt

# Contact address

Contact: mailto:lab@example.net

# Validity

Expires: 2023-12-31T18:37:07z

# Languages

Preferred-Languages: en, es, fr

# Probes description

Description: This is a one-line string description of the probes.

It should be noted that IANA has already added the “/.well-known/probing.txt” URI suffix to its “Well-Known URIs” registry[6].

The RFC also mentions the option of providing identifying information “in-band”, i.e., by including a “Probe Description URI” (URI pointing to a Probe Description File, an email address or a phone number) in a probe itself, in the data field or payload of a packet. In such cases, the URI must start at the first octet of the payload and must be null terminated (and if the URI can’t be placed at the beginning of the payload, then it must be preceded by an octet of 0x00). This means that if one wanted to include a Probe Description URI in packets sent by Nmap, for example, one could do so quite easily using the --data option[7].

To sum up, implementing the recommendations of this RFC might not be a bad idea for those who actively probe third-party systems as part of their research activities, and for security analysts and administrators, it is certainly good to know that this RFC exists, as it might potentially help them distinguish between a “benign” scan and a malicious one.

And while it should be stressed that threat actors might set up Probe Description Files on their servers as easily as anyone else, and blindly trusting information contained in such files is therefore unadvisable, RFC 9511 is still a useful document. As its authors themselves put it, the solution which they came up with “is not perfect, but it provides a way for probe attribution, which is better than no solution at all”[1].

[1] https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc9511.html

[2] https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/html/rfc3912

[3] https://about.rdap.org/

[4] https://isc.sans.edu/data/

[5] https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc9116

[6] https://www.iana.org/assignments/well-known-uris/well-known-uris.xhtml

[7] https://nmap.org/book/man-briefoptions.html

-----------

Jan Kopriva

@jk0pr

Nettles Consulting

Comments